Your manuscript has been accepted by a publishing house. After going over the contract and timeline, the editorial process begins. An editor reaches out to let you know that the first stage, developmental editing, is in progress and to expect an editorial letter soon.

But . . . what is developmental editing?

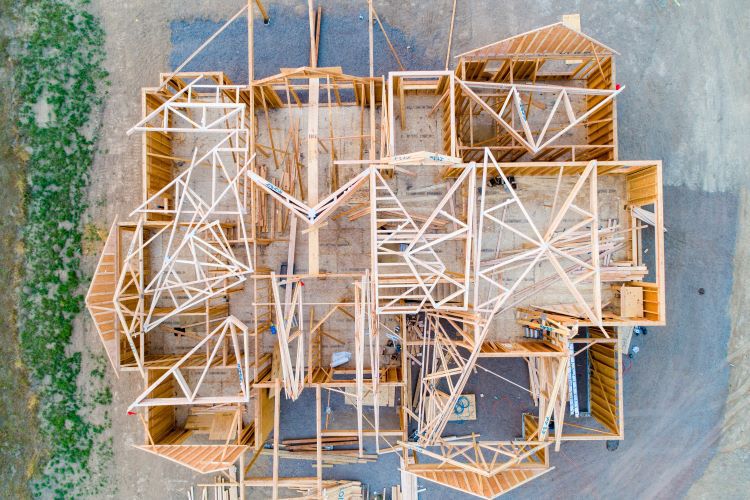

Let’s say instead of writing a book, you’re building a house. While you might already have chosen color swatches and potted plants, those aren’t the first steps. Before any of that can be done, the house needs to have structural integrity—sturdy walls and roof, plumbing and electricity, insulation and ventilation. Before you can place your philodendron, you need sound window sills and running water.

Assessing the structural integrity of a house is what developmental editing is to a manuscript. To be clear, your editor isn’t the one building the house: you are! The editor is somewhere between the building inspector (who will tell you if your house is up to code) and your close friend that you bring by after the initial stages of construction (someone who will tell you, “I love the vaulted ceilings! But don’t we need a door into the bathroom?”). During this stage, an editor isn’t concerned with comma placement, verb agreement, or misspelled words. Developmental editing is an in-depth evaluation of your manuscript on a global scale. Some things that an editor will pay attention to at this stage are plot, structure, pacing, worldbuilding, characterization, and any aspects of your manuscript that might benefit from a sensitivity reader.

When doing a developmental edit, an editor will read your manuscript carefully, taking copious notes and drafting feedback throughout. They will then organize their thoughts and notes into a cohesive document called the editorial (or developmental editing) letter.

What is an editorial letter? It’s not going to just be an itemized list of queries and suggestions. A thoughtful editorial letter is—as the name implies—a letter. The editor will introduce themselves and talk about their experience reading your manuscript, not just as an editor but also as a reader. Your editor might tell you how the suspense kept them on the edge of their seat, or what moments that made them cheer for or shake their head at the protagonist, or how much they loved the dog in the story.

Beyond the opening of the letter, the editor will present the main point or points they are going to discuss in the letter, sort of like a thesis. This might entail strengthening your main character to make them more relatable to readers. It might be altering the dialogue to make it more natural and fitting for your genre. Whatever it is, the editor will provide in-text examples, offer some suggestions, and go through a general problem-solving process with you describing their reaction as a reader, asking your intention as the author, suggesting one or more possible solutions, and inviting you to find other solutions.

In the end, any editorial suggestions editors make are just that—suggestions. We know that the manuscript is yours. We offer advice from both our professional experience as editors and readers, but you are the author. Maxwell Perkins, editor to F. Scott Fitzgerald, said this in editorial feedback of his own to Fitzgerald:

“Don’t ever defer to my judgment. You won’t on any vital point, I know, and I should be ashamed if it were possible to have made you, for a writer of any account must speak solely for himself.”

That advice still stands. In her analysis of Perkins’ editing style, Susan Bell says that Perkins “gave precise suggestions, but preferred to be a dowser indicating the spot where the writer should dig.” This is what thoughtful editors do today.

So, when you get that editorial letter back, know what it is: Not a scathing critique of flaws in your manuscript but constructive feedback from both a reader’s and editor’s perspective. It’s making sure your house is wired so you can have that home theater system you planned for, that your windows are placed to keep the walls strong while still offering you that perfect view of the sunset.

Most of all, developmental editing is an opportunity for you to continue to grow as a writer and to make your manuscript the best it can be.

Blog written by Angela Griffin.