Reading has been linked to learning and developing empathy, but a study published in Cognitive Development in 2015 believes that fantasy stories in particular could be linked to better learning. Whether it’s magic or the supernatural, fantasy elements in stories are as old as civilization, and people in a variety of cultures have found a fascination with the seemingly impossible. Maybe it is time to consider a new benefit to fantasy stories: more success in the classroom.

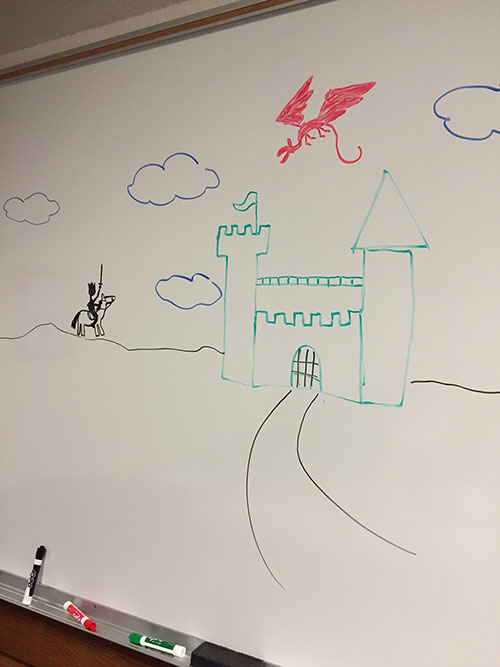

The study looked at how kids learn through storytelling. Deena Skolnick Weisberg and her team at the University of Pennsylvania gathered participants from low-income preschools and used stories and play sessions to teach them new words. One group used realistic stories set on a farm, and the other group used fantasy stories with dragons. Weisberg found that both groups—the realistic story and the fantasy story—showed improved learning. However, the group that learned with the fantasy story had a much more dramatic understanding of the new words. Their conclusion said, “stories focusing on fantastical elements encourage greater learning.”

Weisberg has a few different theories on why the kids showed better learning using the fantasy story. The first is that “fantastical elements may require greater cognitive processing.” Simply put, fantastical details happen outside what is possible in reality. Young readers have to process information that is outside their normal scope of reality, and when that processing takes place, learning happens. In the midst of learning new laws of what is possible in the story, they learn the new words introduced in that story as well.

Weisberg also took into consideration the possibility that “the fantastical story may have encouraged children to think more flexibly,” which helps with problem-solving tasks. Rather than purely learning the words through the stories and games, the children in this group may have had better practice at inferring their meanings by learning new ways to look at meaning through the fantastical elements in the story.

And, of course, Weisberg included the possibility that “books and play materials exploring a fantastical theme may simply be more interesting to children.” Many agree that there is a draw to fantastical stories, and the children in that group may simply have been motivated to pay more attention to the relatively exciting story.

So what does that mean for publishing? Fantasy—along with science fiction, romance, mystery, and other types of genre fiction—usually take a backseat to the highly esteemed literary fiction. It’s affected award winners, author esteem, and book sharing. The debate has been going on for decades, but this study is another check in fantasy’s value column.